In early December, world leaders will meet in Paris to make significant decisions on the future of our climate at the Convention of Parties (COP21) meeting. There has never been a more urgent time to take action on the changes we are witnessing with the Earth’s climate – a warmer world, rising sea levels, and more extreme, unpredictable weather events. The result of doing nothing could be disastrous for both the planet and the human race. The Lancet recently recognized the intricate link that humans have with the planet and the impact we have made: “A growing body of evidence shows that the health of humanity is intrinsically linked to the health of the environment, but by its actions humanity now threatens to destabilise the Earth’s key life-support systems.”

Our food system is not immune to the flux of our Earth’s systems. Food systems contribute approximately 19%–29% of global manmade green house gas emissions, which heat the atmosphere contributing to global warming. Agricultural production, including indirect emissions associated with land cover change, contributes 80%–86% of total food system emissions. To makes things worse, this warming and change in climate will affect our food system including agricultural yields and subsequent food prices, as well as the transport, safety and quality of our food supply. Research has shown that elevated CO2 emissions are associated with declines in key micronutrients such as zinc and iron in the staple crops that many are dependent on for food security and nutrition. Studies also show that the impacts of climate change may slow down progress on both the supply and demand of global food and will surely reverse some of the progress we have made in reducing undernutrition and hunger.

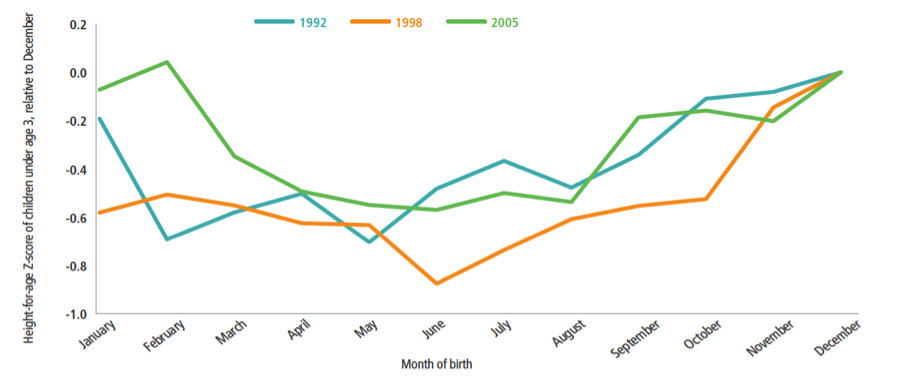

Climate change ultimately affects the nutritional status of populations not just because of food security and dietary impacts, but also because of the increased risk of disease burden that climate change brings (think malaria, dengue, cholera), as well as the reduced access to improved sanitation and hygiene facilities and practices it can cause. Nutritional status is highly dependent on seasons, which climate patterns can alter. The figure below shows the seasonal variation of childhood stunting, a measure of chronic undernutrition. Those who are poor are often more susceptible to this unpredictable seasonality, which is an indicator of a household’s vulnerability to larger climate risk.

Impacts of Seasonality on Stunting (Source)

But climate change is not always the guilty one. Our own dietary choices can impact risks of climate change including land use, and greenhouse gas emissions. Variations in the types of food we eat are driving a new demand for certain kinds of food that are grown and processed in particular ways. This demand will of course be tempered by factors such as climate change and variability, and dwindling ecosystem and biodiversity resources.

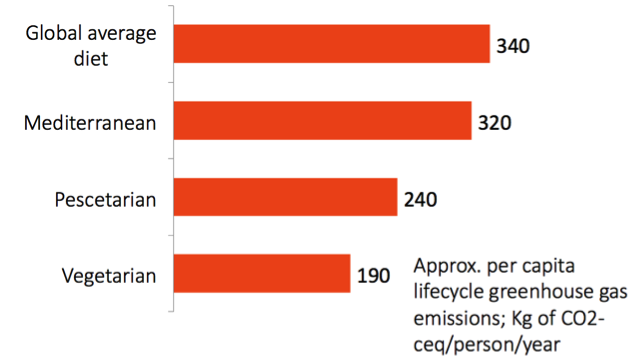

One culprit is animal-source foods. Production of these foods can increase climactic triggers such as the intensification of methane production, which leads to increases in greenhouse gas emissions, with ruminant animals having a bigger impact than those animals (e.g. fish and chicken) whose place is lower on the food chain. Nevertheless, if current dietary trends continue at their present rate, they could fuel an estimated 80% increase in global agricultural greenhouse gas emissions from food production and global land clearing by 2050. Moreover, these dietary shifts are greatly increasing the incidence of non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, cancer and diabetes. The figure below shoes the impact of different diets on green house gas emissions with meat-intensive diets have a larger footprint than vegetarian diets.

Diet Choices Affect Efforts to Mitigate Climate Change (Source)

Projections for the next 10 to 50 years further underline the need to improve the quality and environmental sustainability of the diet. This is especially the case given the challenges imposed by climate change and increasing population growth, in combination with a rising appetite for environmentally costly animal-source foods.

What is clear is that the global agendas for nutrition and climate change are overlapping and complementary. Currently, there is little global cooperation and collaboration, and more can be done together. The International Food Policy Research Institute’s 2015 Global Nutrition Report (GNR) was instrumental as a first step in outlining the issues of the two disciplines. The report went further and outlined key recommendations that could serve to form strong alliances between climate and nutrition agendas while meeting common goals. The recommendations are:

- Governments should include climate change actions and investments in their national food security and nutrition strategies. There should also be a better alignment of government-led national dietary guidelines with planetary boundaries. All to often, diet goals do not incorporate what the global food supply can provide in a sustainable way.

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change should have a nutrition sub-group that can include dietary modeling and scenario building for the next report.

- Civil society groups should advocate for better linkages between nutrition and climate change and ensure that in their work with local communities, they recognize those that are vulnerable to climate change, and seasonality affects of food and nutrition insecurity.

Read the 2015 Global Nutrition Report here. For more information about how we can end hunger and malnutrition by 2025, visit the compact2025 website, produced by IFPRI.