The Gender Gap

Meet the women filling the gender gap in agriculture

CHANDA’S STORY

Training women to take charge of the fresh fruit market in India

Training women to take charge of the fresh fruit market in India

India is the second largest producer of the lychee fruit. But for the women producers tending lychee orchards in the state of Bihar, life was not so sweet. A notoriously difficult fruit to tend, harvest and get to market before it perishes, women in Muzaffarpur were accustomed to leasing their trees to middle-men. These middle-men would harvest the lychee, sell it, and pay the farmers a verbally agreed sum, capturing most of the fruit’s final value for themselves. Often, they only paid a fraction of the promised sum.

In 2016, TechnoServe launched an initiative to help women smallholder farmers participate more equitably in the fresh fruit market, known as the Women’s Advancement in Rural Development and Agriculture (WARDA) program. That’s where they met Chanda Devi.

30 years old and a mother of two, she is the Chairperson of the all-women farmer producer group Samarpan JEEViKA Mahila Kisan Producer Company Limited (SJMKPCL). She was elected to the post by a large majority in 2013 after working as a community mobilizer for over a year, facilitating eleven female self-help groups. Her role included helping them to keep accounts, and keeping them updated on improved farming practices.“When I was voted the Chairperson of the group, I was overwhelmingly happy,” says Chanda. “I never knew I was so liked by my women members. Everyone in my house – my husband, my mother-in-law – was very happy with this news. Being voted as the Chairperson brought along with it many responsibilities to be fulfilled.”

Now, Chanda is helping spearhead the program to ensure women are receiving the technical assistance they need to tend to their lychee trees themselves, allowing them to get the prices they deserve at the market.

“The farmers were unaware of the actual value of the fruit in consumer markets,” says Chanda. “That’s why they found it more convenient to lease their orchards out to middle-men than tending them all by themselves.”

SJMKPCL trained the women on how to irrigate at the right times to maximize soil moisture, to use crop protection products and take good care of the orchards. They were also taught a specific fertilizer regime, that would ensure the trees got the right type of fertilizer at the right time of year and in the right quantity, to promote optimum growth.

In addition, they signed 23 pre-harvest contracts with 130 women farmer members who produced 32 metric tons of lychee, which was sold to big buyers. The revenue generated by SJMKPCL has increased from 0.5 to 2.5 million Indian Rupees in 2017. Over 260 female farmers have been trained on orchard management practices.

Chanda herself knows the value that increased income can bring to a family. She first applied for her role as Community Mobilizer when her family was struggling to survive on her husband’s income from his one-hectare cereal farm. She attributes her success to the support of her family.

“Women, when given the right opportunities, are most likely to seize them and become successful at the same time,” she says. “The most important factor, however, in them being successful is the support from their family – especially her husband and in-laws.”

But the benefits do not end there.

“The women members who have benefitted from the group are now more vocal about their concerns that they face both at their homes and farms. They are more confident as they have learnt how small savings, when combined, can bring big fortunes.”

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

“South Asia has one of the lowest rates in the world of women’s participation in the labour force,” says Anja Rabezanahary, who works on gender and social inclusion at the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD).

“Less than 35 per cent of women are engaged in paid work. While agriculture employs over 60 per cent of the economically active women, they comprise only 35 per cent of the total agricultural labour force. Only 7 per cent of farm holders are women. Women are generally far less able to access extension services, credit and production assets.”

“Norms and traditions in South Asia still exclude women from profitable economic opportunities. From an early age, gender ratios are skewed owing to a continued preference for boys in society, at least in part because of the dowry system,” she adds.

“Women in South Asia are key actors in agricultural production and processing. However, value chain development activities can result in men taking over profitable activities performed by women, or confiscating the income these activities generate. Women’s decision-making power in the household is low compared to other Asian regions. For instance, only 57 per cent of women in the poorest quintile have some say in deciding on visits to relatives. The percentage is higher in richest quintile and goes up to 71 per cent.”

“More women like Chanda can be empowered. To do this, self-help groups need to be further strengthened to increase decision-making and economic power of women. The groups offer a safe place for discussion, and women hold control of working capital and profits, preventing them from appropriation by husbands and male relatives.”

“Second, women-specific value chains must be supported by providing microcredit, technical and social trainings to improve household-level gender relations.”

“Dedicated human resources for gender issues at IFAD have improved gender outcomes, advocacy and networking. For instance, in India, country-level gender coordinators have provided direct support to project design and supervision and convened annual gender network meetings of IFAD-funded project staff.”

SDGs covered:

Case study prepared by: TechnoServe

Commentary provided by: IFAD

Photo credits: Suzanne Lee

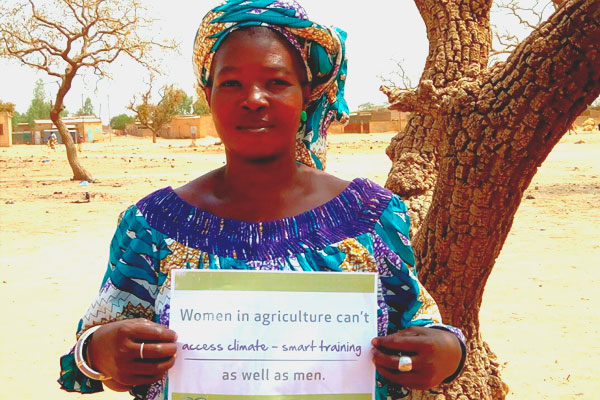

HABIBOU’S STORY

Using storage and seeds to get climate-smart in Burkina Faso

Using storage and seeds to get climate-smart in Burkina Faso

Habibou is the sole provider for her four children. Since her husband went blind, he has not been able to work on the family farm.

She lives in the Oubritenga province of Burkina Faso, and managing her farm of millet, maize, sorghum, beans and groundnuts has become increasingly difficult. Over the past 30 years, average annual rainfall has dropped by 200 mm here.

“I see a real change in the climate. Before we had rain. This year, the rainy season started well but now the rain has stopped. This is a real problem for us. If the land is dry, we can’t work and have to go home,” Habibou says.

Training on how to cope with these challenges does not always reach female farmers like Habibou. But the BRACED project, run by NGO Self Help Africa and partners, including Welthungerhilfe and local organizations, is supporting more than 600,000 people in several regions of Burkina Faso to become more resilient to such climate extremes, with a particular focus on female farmers.

Habibou received improved bean, maize and sesame seeds from the project. “Those seeds grow better and more quickly. I used to grow the same crops before but didn’t harvest as much,” she says.

Learning about conservation agriculture has been instrumental in helping Habibou to grow more. “Before the training, I used to just clear the land and throw the millet seeds. Now I know how to dig small holes and plant the seeds in a line. I noticed that I produce more crops with this new method,” she says.

Habibou also learnt about the benefits of keeping her crops in a storage room to protect them from sunlight. Now that she is able to keep her crops longer, she waits until the market price is high before selling them, meaning she gets a higher income from her produce than before. Similarly, she was assisted in the building of a henhouse to reduce the risk of her chickens running away and to provide a safe space for chicks to grow.

Like most women in her village, Habibou used to gather wood for cooking purposes. But she has since learnt that it is an unsustainable practice. “Wood as a resource is becoming scarce, because we cut a lot of trees for cooking in the past. It is also contributing to the erosion of the soil, we should in fact plant trees as they help retain water in the soil.”

Habibou volunteered to attend training on how to build improved cooking stoves. She is now teaching other women in her community how to change their cooking practices.

The knowledge that she has learnt, and the new practices she has put in place, has made Habibou and her farm more resilient to future hardship. She has passed on this knowledge to her children and, thanks to an increase in her income, she has been able to keep all of her children in school. Her eldest daughter, Fatimata, who left school after she got pregnant, has now returned to school and hopes to go to University to become a doctor.

“I am positive about the future,” says Habibou. “My children see what I’m doing now on the farm and they are aware of that. Because they go to school I think they’ll have the opportunity to do more than me in the future. If they don’t want to work in farming, they’ll be able to find good jobs and to take care of themselves.”

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

“It is critical that governments commit to addressing the gender gap if we are to have a food secure Africa,” says Lindiwe Majele Sibanda, Vice President of AGRA. “We know that while women do the lion’s share of the agricultural work in sub-Saharan Africa, they are not receiving their fair share of the resources and training. This in turn puts a heavy cost burden on society in terms of lost agricultural output, and economic growth. Closing the gender gap should be viewed as a business priority and an economic imperative.”

“As well as farmers, rural African women are stewards of the land. But in settings where women – often poor women – have limited access to resources, restricted rights, limited mobility and limited voices, in decision-making at community and household level, they become even more vulnerable.”

“Research shows that women are less able to access climate-smart training than men. AGRA’s efforts are changing this reality. Since we started our work in soil health in 2008, we have seen 1.7 million farmers adopt climate-smart practices like integrated soil fertility management (ISFM) on over 1.6 million hectares of land. Out of these, over 60 per cent have been women.”

“If we empower more women like Habibou, we will see a domino effect in African communities. Because if a woman is more productive, her increased income will be spent on the education, health and nutrition of her children. In order to do this, we must ensure that women can make decisions on production, access and deployment of resources such as land, use of income and time allocation.”

“Passing laws that ensure women have equal access to land, inputs, seeds, extension and financial services, post-harvest facilities and markets will be critical. In addition, governments should seize opportunities for innovation and make technologies, equipment and inputs for women farmers more accessible through flagship programs or subsidy programs that can get women farmers on their feet.”

“We also need more public private partnerships that ensure more and more unbanked women are banked can access credit and have control over use of income.”

SDGs covered:

Case study prepared by: Self Help Africa

Commentary provided by: AGRA

Photo credits: Self Help Africa

JOYCE’S STORY

Women take the lead in protecting Tanzania’s trees with forest-friendly businesses

Women take the lead in protecting Tanzania’s trees with forest-friendly businesses

The Nou Forest in northern Tanzania covers 320 square kilometres. It is a source of 28 permanent rivers and directly affects the livelihoods of more than 200,000 people, making its conservation vital.

Yet to cope with low productivity of land, farmers in Tanzania still turn to forest clearing to meet demand for food production. In the case of the Nou Forest reserve, this has led to soil erosion, silting and bank erosion of streams. Various tree species have also been threatened.

Joyce Lali, a 45-year-old mother of seven from Erri village, is working to ensure that the forest she derives her livelihood from stays intact.

She is the Secretary of the Erri Jigegemee Beekeeping Group that produces a wide range of food, health and beauty products from honey.

“Formerly, we didn’t know about the value of forests. We were cutting down trees and didn’t realise how important trees were. But then we started beekeeping and now we realise it is important for us to preserve the forest for the bees. Now we earn an income from forest products,” says Joyce.

Historically in this village, women were not economically active and were largely dependent on their husbands. While men have been involved in honey production in this area for years, they used traditional beehives suspended high in trees. Women were not able to take part as it was culturally unacceptable for them to climb trees.

The NGO Farm Africa has been working with the community in Erri village to earn money from the forest while protecting its resources for future generations. They introduced Langstroth beehives that sit on the ground, so women are now able to engage in honey production too.

“Before, we couldn’t speak in community meetings, but now we do,” says Joyce. “Before, we were oppressed by men and we didn’t earn any of our own money, we just stayed at home and looked after our children. Now women can participate in various meetings in the community, we have different groups and we learn from each other. Previously, it was chaos in the family because as a woman if I needed anything, even something really small, I had to request it from my husband. Now, I have my own money and I can buy the things I need myself.”

The group focuses on adding value to their honey, making products such as sesame and honey cakes, honey medicine, dried mushrooms, water, sesame tea, beeswax candles and face creams made from honey and seeds.

“The money I earn means I can send my children to school and I also save money by making products like soap, so I don’t have to buy them in the shops any more. We have been able to renovate our house. Previously we lived in a house with a thatched grass roof. Now we have a roof made from iron sheets. The major thing is that now we are able to pay our children’s school fees.”

The co-operative has constructed a marketing stall, which they take to exhibitions to market the products. Following discussions with Farm Africa about how certification of products can add value and open up access to wider market, the group is now investing in the construction of a new processing centre for their honey, so they can meet the standards set by the Tanzania Bureau of Standards and the Tanzanian Food and Drugs Authority.

Their entrepreneurial spirit doesn’t stop there. Building on the success of the marketing skills they have learnt, Joyce and her team have now also started filtering and marketing mineral water. They have bought a water filtration system, which they use to filter water from the Nou Forest and sell locally to people needing water for events and celebrations such as weddings and communions.

“I send special appreciation to Farm Africa as an organization for making us women seen. Before, we were invisible in the community. They have helped us increase the value of females in the community,” says Joyce.

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

“In Tanzania, it is estimated that the agricultural gender gap costs US$105 million annually,” comments Natalie Kostus, Executive Vice President of the International Alliance of Women.

“Across East Africa, women like Joyce are impacted every day by practices and beliefs that limit their access to productive opportunities and natural resources. They are perceived by the community to lack knowledge, skills, and strength to participate in forest programs.”

“In many cases, even if the national law grants land rights to women, traditional and customary practices preclude women from accessing, owning, and inheriting the land in this region. This puts women at risk of losing resources and benefits, such as payments for environmental services.”

“Women like Joyce need to have clear ownership rights to forests and forest land, necessary for the active socio-economic participation of women in forest management, conservation of biodiversity, climate change adaptation and mitigation, and emerging opportunities, such as carbon trading.”

“It is also crucial they have productive work and financial security; raising their voice and power in household and community decision-making, organizing women’s groups supporting and learning from each other, accessing technology, and sending their children to school, benefiting the whole community. A needed initiative is training on women’s rights for women and men in the village, including traditional leaders. This will go a long way to closing the agricultural gender gap in East Africa.”

SDGs covered:

Case study prepared by: Farm Africa

Commentary provided by: International Alliance of Women

Photo credits: Farm Africa / Jon Spaull

CELIA’S STORY

Using plant science to fight pests in the Philippines

Using plant science to fight pests in the Philippines

Mangoes are the national fruit of the Philippines and are grown by around two and a half million smallholder farmers on over 7 million mango trees. They are a high value crop and provide a huge boost to the rural and national economy.

But the hot and humid temperatures that are ideal for growing mangoes, are ideal for the spread of pests and diseases.

Protecting Filipino farmers’ mango harvest is Celia Medina’s inspiration.

She was born in Saint Valles, a province well known for its mangoes. She followed in her parents’ footsteps, who both carried out research on mango selection.

“I was born to and brought up by a woman who built her career in agriculture so I had no doubt that women have a place in agriculture,” Celia says.

But the path was not always easy. In high school, girls were required to attend home economics classes, while boys studied agriculture. Determined that she could do as her mother did, Celia joined the boy’s curriculum.

“Being the only girl in the class was not easy. But, my teacher Mr. Renato Ruba, was so protective of me. My classmates showed animosity at first, but I was treated as one of their own league even before the end of the first year.”

Celia is now an associate professor at the University of Philippines Los Banos. As an entomologist, Celia studies the interactions between plants and insects. By understanding the insects, she is able to manage them and help farmers increase their yields.

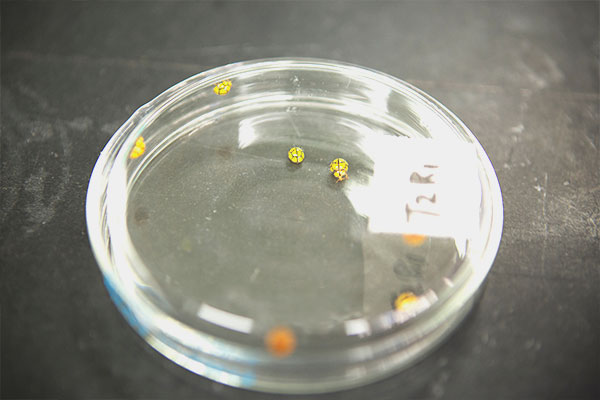

Recently Celia has been investigating the usage of biological control methods to combat a common mango pest – the leaf hopper. During mango season, up to 90% of yield can be lost if leaf hopper destroys the fruit’s flowers. She is currently looking for natural predators that will be compatible with pesticide use.

The most effective natural predator of mango pests is the yellow nettle lady beetle; last year scientists released around 200 per hectare at mango farms in the Philippines. One individual beetle can consume up to 60 mango leafhoppers a day.

“I get involved with many farmer associations. I get to know the needs of farmers and how they think, their psychology. I have seen their weaknesses, their problems and I would like to change it.”

Training farmers in the fields has also proved challenging for Celia in the past. Male farmers that were much older than her, tended to doubt what she had to say.

“Back in the year 2000, while doing a field survey of fruit fly, I met a retired farming teacher who asked me point-blank if I knew what I was talking about. Later in that year, he attended a training I conducted. At the closing ceremony, he gave a testimonial speech where he told the audience how he insulted me the first time he met me and asked for an apology with teary eyes. That was touching!”

Celia is now working to train other young scientists to find the solutions to help Filipino farmers thrive in the face of new challenges such as climate change, and pests and disease.

“I am a teacher as well as a researcher, and I know that I am shaping the minds of young people who can also continue my work. That gives me energy every morning to get up.”

“If I leave something in this world, I want to leave it for my home province.”

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

“Scientific research can transform lives, particularly the lives of women who play a critical role in food production, post-harvest processing and across the value chain,” comments Geoffrey Hawtin, International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) Board Chair, Center Board Member for the CGIAR System Management Board, and gender research champion.

“Scientific interventions are helping to reduce women’s drudgery, improve their access to information and agricultural innovation, increase their decision-making powers and incomes, and strengthen their land tenure rights, producing a ripple effect for entire households and communities as a result.”

“To give just a few quick examples, the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat has made it easier for women to obtain small loans, while improving access to inputs in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Sudan. “

“Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, training sessions are enabling women to engage in agricultural value chains, and guidelines have been produced to ensure that women have better prospects for taking advantage of agribusiness opportunities. In West Africa, new parboiling technology developed by the Africa Rice Center is reducing the work burden of rural women, while improving nutrition and attracting higher prices at market.”

“On this International Women’s Day it is worth reflecting that one of CGIAR’s key goals is for there to be 150 million fewer hungry people and 100 million fewer poor people by 2030 – at least 50 percent of whom will be women. These and other CGIAR objectives make a strong contribution to meeting the Sustainable Development Goals.”

“Only addressing the challenges of female farmers however is not sufficient, and the engagement of women in science and leadership is just as important,” concludes Hawtin.

“The CGIAR System Management Board recognizes the importance of gender in the workplace, and the need for dedicated activities in this area, particularly ensure that the CGIAR System is gender diverse, equitable, and encourages inclusive workplaces.”

SDGs covered:

Case study prepared by: CropLife International

Commentary provided by: CGIAR

Photo credits: Guilhem Alandry

GRISELDA’S STORY

The woman planting seeds for a better future for Guatemalan potato farmers

The woman planting seeds for a better future for Guatemalan potato farmers

In the Western Highlands of Huehuetenango and San Marcos in Guatemala, potato farmers have used recycled seed for generations, a tradition that is passed from father to son.

However, these recycled seeds are leaving crops susceptible to pests, diseases, and other viruses. Certified seed can triple potato yields and help farmers increase incomes from potatoes by up to 300 per cent. But convincing farmers of this remains a great challenge in the region.

Griselda Velazquez is taking the lead in making sure that better seeds are available to create a better future for these potato farmers. She is responsible for the production of certified potato seeds at the Guatemalan company Servicios de Post-Cosecha, managing a team tasked with seed reproduction and transplanting of plantlet. As team leader, she oversees quality checks to ensure consistent seedling production and multiplication.

“The market continually demands higher quality products, so the demand for certified seed is increasing too, so that farmers can improve production and raise their incomes,” comments Griselda.

When she was hired, she was the only woman working at Post-Cosecha, and soon became faced with colleagues who believed a woman could not handle this type of technical work.

“Only men worked in planting, cutting, or transplanting, and they believed that when this work was done by a woman, the plants were more likely to die.”

Griselda overcame this challenge through openly but assertively communicating with her team. She organized a meeting with her group that allowed space for a dialogue. She explained that she was going to lead the group, and needed respect in exchange. After the dialogue, the group better understood that women had the right to be leaders, to express their opinions, and to conduct managerial and technical work. Now, there is another full-time woman and five temporary ones.

“We are showing that women can break gender stereotypes related to agriculture through direct training in the fields, and our work introducing quality seeds,” Griselda says.

“Because of the Guatemalan culture to pass seeds from father to son, it is hard for women to get good quality seed. We are now introducing good quality seeds to organisations, and particularly women farmers.”

Griselda’s boss, Andres, has been a supportive mentor since day one. He provided her with recommendations on how to handle the early resistance from her team and used his authority to lend her greater credibility with skeptical groups. He placed his trust in her and encouraged her professional growth and supported her as a leader.

“I encourage rural women to break those gender stereotypes, and overcome these challenges in agriculture,” says Griselda.

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

“As the former President of Costa Rica, Mrs. Laura Chinchilla once said, there is no social sector more invisible, less understood and less served, than that of rural women, despite the vital role they play in our rural communities,” says Miguel García-Winder of the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture.

“Several estimations indicate that rural women in Latin America and the

Caribbean (LAC) are responsible for the production of approximately 45 per cent of the food consumed by rural households in the region. Additional to their role as producers, they have important roles selling surplus produce and running their homes, as well as beingcommunity leaders, mothers and wives,” he adds.

“To add to this, rural women in LAC confront other obstacles that limit their development and prevent the full expression of their productive capacity. One of the most important challenges is the access to education. For example in Guatemala, more than 60 per cent of rural women dedicated to agriculture cannot read or write. There are countries in the region that have been able to bridge this gap, Chile is probably the best example where this percentage is only 6.7.”

“Inequality in labour conditions and access to work opportunities; lack of access to productive inputs, particularly to land ownership; and insufficient access to credit all limit the development of women in the rural areas of LAC. These challenges have resulted in increased migration to urban areas, particularly by young women, where they become prone to exploitation and in several cases to new forms of slavery.”

“Griselda’s story show us how powerful providing education, productive opportunities and the development of leadership abilities can be. However, it also points to probably the most critical issue, which is the need to transform old cultural and socio-economic norms and patterns.”

“Public policies to improve extension services are needed, and better education and labour markets are needed too. But what we need the most is to recognize that women and men are equal, that they deserve the same rights, the same treatment, the same opportunities. LAC needs a new generation of women like Griselda, but also needs a new generation of men that work side by side, equal with women, to make this a better world and to preserve our mother Earth for future generations.”

SDGs covered:

Case study prepared by: Fintrac

Commentary prepared by: IICA

LUBOV’S STORY

The female CEO opening up new markets for Ukrainian farmers

The female CEO opening up new markets for Ukrainian farmers

When the Soviet Union fell in the early 90s, Lubov Semenyuk found herself in charge of a food factory that was no longer profitable. After her director and finance director resigned, it was up to her to turn the business around.

“After our huge, 400-employee enterprise had collapsed, I analysed the reasons and, starting a new enterprise, set myself a goal – to prove to myself and the others that I can run business in Ukraine legally and transparently,” says Lubov.

“I was passionate to make a change in the old food processing business in my city. My mom, being a farmer herself, made me curious about the food that farmers produce. It was my inspiration.”

She decided to divide the business into three smaller businesses, which would allow each one to better pay their taxes, pay a living wage to their employees, and allow space to grow and thrive as businesses. This was no small task; her former bosses continually urged her to give up and the economy continued to be mired in corruption.

18 years later, the Vinnytsya Food and Gustatory Factory is one of the leading enterprises in the region in the sphere of food and vegetable processing. In 2014, the company successfully passed an international audit for FSSC:22000 certification, ensuring access to international markets. The mission of the company is to produce high-quality natural and safe products at affordable prices.

Ms. Semenyuk graduated with a Diploma with distinction (the equivalent to a combined Bachelor and Master degree) as an Engineer Economist from the Odessa Technological Institute of Food Industry during the Soviet era. But it’s her business acumen that has helped the Vinnytsya Food and Gustatory Factory thrive since she took the helm.

“As a woman in a man’s business world, I have to be very focused and active,” says Lubov. The only way to make people follow you as a leader is to show them your commitment and result-orientation. I am really proud that, over the years, I have built very trustworthy relationships with male partners.”

In addition, Lubov has helped other women enter the agribusiness workforce, by providing them with a market.

Most of the small farmer suppliers of the Vinnytsya Food and Gustatory factory are women. During the growing season, a truck goes to villages to take raw materials from farmers. Every day, 30 village collectors buy up to three tons of horseradish from private households in Vinnytsya, Khmelnitsky, Lviv, Ternopil, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Zakarpattya oblasts.

“Ukrainian women are mainly engaged in low-paid economic activities in agriculture, and that type of work is much harder. Therefore, it is important to support females in opening new markets for them,” says Lubov. “Hard work should pay off!”

“Ukrainian women are very hardworking, but with a lower level of confidence in themselves,” she adds. “I would share with them my simple advice: believe in yourselves and lead the team by your example. Women can do anything, simply because it is from the bottom of their heart!”

The USAID-funded Agriculture and Rural Development Support (ARDS) project is now supporting Lubov and her business to expand markets for these farmers. By co-investing into equipment for updating the factory’s bottling and packaging line for sauces and spices, the project will increase efficiency, expand the range of products produced and improve working conditions.

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

“According to the World Economic Forum’s 2016 Global Gender Gap Report, Ukraine ranks 69th out of 144 countries on closing the overall gender gap between men and women,” says Galyna Skarga, Head of the Union of Rural Women in Ukraine. “In the area of Economic Participation and Opportunity, Ukraine is closing the gap with a score of 70 per cent parity, but change is slow (in 2006 the same sub index was 68 per cent).”

“Most women in Ukraine are engaged in low-paid economic activity for historical reasons. Men were fighting or hunting and women were taking care of their homes. It remains the same now: for the majority of the population, especially in rural areas, a woman should be engaged in household chores, children, and family. This type of work is low-paid.”

“Rural Ukrainian female farmers have difficulty accessing markets for their produce because they are less likely to have a driver’s license than their urban counterparts. Even if a woman did have a driver’s license, it is unlikely she would be comfortable driving large truckloads of produce to markets. Many rural citizens sell to wholesalers because if the wholesaler will come to pick up the produce, the farmer does not have to transport it. The wholesaler then takes on any processing and gains the added value. Currently, few rural processing centres exist for rural women to access.”

“Lubov’s story is a very bright and inspiring example of woman-leader in agricultural sector. Agricultural business is mainly dominated by men in Ukraine, and Lubov is a good model for other women to follow her way, especially for rural women.”

SDGs covered:

Case study prepared by: Chemonics

Commentary provided by: Union of Rural Women in Ukraine

Photo credits: ARDS Project